Vestas & beyond: missing our green energy opportunities

July 30, 2009 at 8:09 pm | Posted in British Politics, Climate Change | 1 Comment

The other day, a friend asked me to tap a few words in support of the protests by workers at the Vestas wind turbine factory who’re trying to stop the loss of over 600 jobs and a potentially important resource for expanding renewable energy. Whilst that support is freely given and sincerely felt, the circumstances of the case have been so widely–stated and well-documented elsewhere that I don’t want to spend too long restating the obvious.

It’s clear that Vestas has acted with contempt towards its workers: the practically non-existent dialogue, the transparent attempt to starve them out, the delivery of termination letters with the workers’ one hot meal, the shoddy paperwork filed to have them evicted, and the laughable charge from their legal team that there was a fear the protests could get ‘heated’ or violent.

Equally, whilst Ed Miliband has handled the matter better than one might’ve expected, the charge that his government has lacked leadership on this can’t be ignored. Whether the option is nationalisation or, more preferably, a kind of decentralised, locally-run operation, there is a case for the government to facilitate some kind of deal to save the factory.

But I’d now like to leave the particulars of Vestas’ closure to one side and try to consider the case from a national perspective.

The common purpose shown by the pro-labour left and the green movement (and obviously there are overlaps between the two), comes from two sources. First, concern for the livelihoods of workers at risk of unemployment and disgust at how they’ve been treated, but also from a wider feeling of anger & frustration at what many activists feel has been a lack of resolute commitment by the government to tackle climate change and remodel our system of energy production.

Those activists have a point. However, so does Miliband when he argues that government shouldn’t shoulder the entire blame for the lack of progress on wind farms; many councils have been resistant or hostile to planting turbines in their back yards, and many community campaigns have succeeded in having plans to build one in their area aborted. If the green movement – and the general public – is serious about seeing wind power as part of our energy future, then solely lobbying central government isn’t the way to go.

So the fault is partly on this government, partly on us for resisting change, and partly on the failure of green activism to make a grassroots case for why action is necessary and what rewards can be reaped.

For me, this all rather underlines the urgent need to be more radical about clean energy, and for government to create the conditions which make it easier for us all to take ownership of spreading green technologies. If we could really push forward with the ‘smart grid‘, take greater steps to decentralise electricity production & distribution, and incentivise micro-generation , you might just see more switched-on (pardon the pun) energy consumers.

Let’s just take one example from abroad. Denmark is currently the biggest source of wind power in Europe, but to get to that position it encouraged the public to invest in it; offering tax incentives for people who either generated their own electricity or as part of a commune. Eventually wind turbine cooperatives became commonplace, with individuals being able to own a stake in the power being produced. In 2004, over 150,000 Danes either owned turbines or shares in a turbine cooperative.

Could this not work in Britain? If there were genuine economic incentives as well as environmental benefits for individuals & communities embracing wind power (and green energy more generally) would the resistance to them really be so great? The advantage of these reforms is that it could enable the general public to become more involved, but first the government needs to create the conditions & incentives for it to happen.

Again, aside from the specific cruelties of the Vestas case, it should seen as reflective of a sense of frustration about Britain’s environmental and energy future. To turn that into positive action, our best hope might be to (quite literally) put power in the hands of the people.

Vote Rantzen!

July 28, 2009 at 2:20 pm | Posted in British Politics | 6 CommentsBecause the woman behind this…

Is obviously far more principled than Margaret Moran.

Hague’s vision for British foreign policy

July 28, 2009 at 10:45 am | Posted in British Politics, Conservative Party, International | 6 CommentsOn paper at least, William Hague seems like he could be a qualified & competent Foreign Secretary. Ideological differences aside, the former Tory leader is regarded as one of the smartest men in his party, is a keen debater and someone who apparently possesses a strong interest in, and grasp of, British history. These qualities (particularly the last) are all important in a top diplomat, and I think it’s safe to say they have not been present in every one of Labour’s foreign ministers.

Likewise, the vision Hague recently articulated for the future of British foreign policy is – again, on paper – a positive start, and one which does well to reflect both the global economic realities of the present and the breadth of challenges our government will face in the future. You should read Chekov’s excellent post for a summary of what was said, but the tone & themes of Hague’s speech seemed to suggest a return to a Realism or Liberal Realism which would be a welcome break from a Blair doctrine we cannot afford – either financially or diplomatically.

By embracing a more realist approach, Hague can reconcile the traditional Tory emphasis on the sovereignty of the nation state and aversion to grand global designs with a promotion of British values by means of diplomacy, trade and cultural dialogue. Using these means, the Tories would hope to restore those relationships which have corroded in recent years, whether with superpowers such as Russia or the smaller, fractious states in the Middle East where we used to have considerably more influence and respect than we currently possess. As Chekov notes, the worth of any new policy can only ever be judged by how it’s implemented but, if his vision is realised, we should at least avoid the kinds of interventionist escapades which have blighted the past decade.

But there are still some significant omissions from this speech, and problems with other statements the Tories have made in opposition. The first omission regards how his government will approach the arms trade, which has snared previous Conservative governments in scandal. As much as the Tories see free trade as a means to healthier diplomatic relations, the kinds of regimes our manufacturers sell arms to does reflect on our country’s reputation. For that reason, it’s to be hoped that – recession or no – David Cameron will make good on the commitment he made over three years ago to be tough on British manufacturers who provide arms for the world’s bloodiest conflicts.

Whilst Hague promised a comprehensive review of defence spending, he was frustratingly tight-lipped on what vision the Tories have for the future of the armed forces. Given the budget crisis and his more modest appraisal of Britain’s place in the international community, it would be nice to have received an indication that we should therefore be funding a different kind of military. In particular, beginning a shift away from funding a force built for conventional warfare, and towards combating unconventional, terrorist & economic threats (as suggested by this IPPR report) would be welcome. There is still, to my mind, no strategic loss if we failed to renew Trident.

The old issue of Europe still looms large over the party, and whilst the long-term consequences of Cameron’s decision to withdraw his MEPs from the centre-right EPP are still unknown, those voices (even within his own party) who warned that Cameron was making the biggest mistake of his leadership have so far not been proved wrong, judging by the ‘interesting’ company they now keep. Meanwhile, the Tories’ admirable (and slightly surprising) commitment to maintaining our foreign aid contributions has been spoiled by proposed reforms which appear to privilege Whitehall bureacracy over on-the-ground local planning, and feature a bizarre and slightly degrading internet democracy component

Another concern I have is the role a Prime Minister Cameron will play in setting Britain’s foreign policy. Over the past year or so, Cameron has shown a tendency to overreact to world events: his intervention in Georgia last year was anything but the kind of nuanced diplomacy promised in Hague’s speech, and his naive approach to the uprising in Iran would’ve been disastrous had he been Prime Minister – lending a scrap of legitimacy to Tehran’s paranoid ramblings about foreign agents trying to influence the country’s affairs. For a man who three years ago wanted to see a return to ‘humility & patience’ in Britain’s foreign policy, it’s yet to be seen whether Cameron possesses the temperament to see that through.

So whilst Hague’s words about the path the Tories will take on international relations will hardly fill even the Conservatives’ sharpest critics with dread, there are still many outstanding questions to be answered and many unknown tests that his government will have to face. They might not repeat the mistakes of the Blair era, but that’s not to say they won’t make a whole load of mistakes of their own.

Friends of the Honduras Junta

July 24, 2009 at 3:22 pm | Posted in International, U.S. Politics | 2 Comments

Meet Jim DeMint. Jim is a United States Senator from South Carolina, one of the most conservative members of Congress and a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Silly Analogies.

Worried that Barack Obama might merrily lead his country to dictatorship, DeMint has claimed the administration is eerily redolent of Orwell’s 1984; has suggested that America now resembles Germany just before WWII; and has speculated that the Hopey One may – in the words of ABBA – finally be facing his Waterloo. He’s also protested Obama’s habit of exporting his tyranny abroad, supporting “despots like Ahmadinejad, Chavez, Castro” and the ousted Honduran President Manuel Zelaya.

The removal of Zelaya from office by Honduras’ miltary (which I’ve discussed here & here ) was condemned by the Obama administration but gleefully embraced by conservatives like DeMint, who insists that the ‘transition of power’ in that tiny, impoverished country was no more of a coup than Gerald Ford’s ascension to the Presidency or Al Franken’s recent election as Senator for Minnesota.

‘Interesting’ comparisons, I guess, except that Gerald Ford lawfully assumed the Presidency after his predecessor turned out to be a crook, whilst Manuel Zelaya was bundled out of the country at gunpoint whilst dressed in his pajamas. As for Al Franken, well, he at least won a slim majority of the votes in Minnesota; the Honduran junta has yet win the votes of even its closest family members.

But whilst it’s always fun to point & laugh at preposterous little hacks, the reason I highlight DeMint’s mad ramblings is to demonstrate that despite the Obama administration taking the correct position in denouncing the coup, the country still bears some responsibility for its origins and its continued existence.

Earlier this month, supporters of ‘President’ Roberto Micheletti hired two lobbyists to massage the American political class into viewing it, perversely, as a victory for democracy. Both Lanny Davis and Bennett Ratcliffe had previously held important roles in the Clinton administration, and Davis was a vocal supporter of Hillary Clinton during the Democratic Party’s Primaries. In Congress, an informal ‘coup caucus’ has emerged, with the apparent aim of unifying the message they use to sell the junta’s actions. As others have noted , the American media’s response has also left a lot to be desired, with anti-Zelaya bias noticable in a great deal of the reporting & commentary – this editorial by the Wall St. Journal even had the temerity to call the coup ‘democratic’. The aim of this lobbying is simple; with Honduras so reliant on the international community for aid and the huge export market of the United States, America could exert real pressure on the illegal regime. As such, the best way for this motley crew to maintain power is for domestic pressure to be placed on the Obama administration in the hope of restraining it from fully exerting its own power.

Then, of course, there’s the issue of the American military/intelligence communities and their decades-old influence in the region. I think it’s generally accepted that CIA interference in Latin America is not what it was, and has reduced considerably since the days of Kissinger. However, it’s still the case that several key figures in the coup, including the leader, General Romeo Vasquez, were trained at the US-funded School of the Americas . On top of this, the country continues to receive training & millions of dollars in military aid, ostensibly for the purpose of combating drug trafficking. So the United States may not have permitted or endorsed this coup, but it did, albeit inadvertently, fund and train those who carried it out.

For the Obama administration, Honduras represents a number ironies. On the campaign, Senator Obama promised a different approach to Latin America; one which was more collaborative than coercive and which saw the decades of overt & covert interference from successive administrations come to an end. Now as President, he can see two large obstacles towards achieving this. First, such is the U.S.’ long history in the region, his office doesn’t actually have to do anything for the United States to be somehow implicated in events. Second, after years of wishing for the more collaborative relationship he promised, I think there’s now a trend in Latin America towards wanting to America to resume its position of regional leadership. Even the frequently combative & combustible Hugo Chavez recently sent Obama a simple, but rather surprising, message on the crisis: “do something.” For a man who has fancied himself as something of a regional powerhouse, that’s quite some deference.

With talks between Zelaya & Micheletti’s representatives still in a seemingly intractable stalemate and the deposed President once more seeking to return to his country, I doubt this conflict’s going to be over any time soon. But the events in Honduras demonstrate that presidents don’t always have the luxury of choosing their own foreign policy or even making a completely clean break from the past. Sometimes you just have to make the best of what other people have handed to you, whether that’s grouchy, paranoid Republican Senators, or small, poor & volatile South American states.

Image: A supporter of Honduras’ ousted President Manuel Zelaya holds up a placard with a picture of Honduras’ interim President Roberto Micheletti during a road blockade on a highway on the outskirts of Tegucigalpa July 23, 2009. Zelaya’s supporters called for a two-day national strike on Thursday and Friday to demand his return, and say they will also set up roadblocks across the country. Around 1,000 people blocked a road on the northern outskirts of Tegucigalpa on Thursday, burning tyres and causing a tailback of trucks. (Source)

The Mercury Prize

July 22, 2009 at 10:07 am | Posted in Music, Art, Etcetera | 12 Comments There’s a special time, which only comes once a year, where music fans, bloggers & journalists all get to gather in their pubs, clubs or online communities and stage their own re-enactment of this toe-curlingly true scene from High Fidelity:

There’s a special time, which only comes once a year, where music fans, bloggers & journalists all get to gather in their pubs, clubs or online communities and stage their own re-enactment of this toe-curlingly true scene from High Fidelity:

I am, of course, talking about the announcement of the nominees for this year’s Mercury Music Prize, an award which is as important to the British music scene as it is maligned by a large number of the folks who follows it. Every year you can witness the same ritual of fans quibbling with the choice of nominees, complaining that their favourite record isn’t in the mix, whinging about the perceived ‘tokenism’ of always including a folk or jazz act, or tossing around charges of ‘selling out’ to ‘the man’. The sad truth is, many of us perversely enjoy this week-long round of fault-finding, and it at least demonstrates the depth of passion people still have for individual bands & records even in an age where the monetary value of music has decreased but its availability has exploded.

But the reason the prize is criticised isn’t just driven by pedantry, fandom & snobbery (though they all abound at this time of year), and I think there are valid questions to be made about whether the prize should really be sustained in its current form.

The Mercury Prize is still the most prestigious and high-profile award for independent or alternative music, but it’s seeking to represent a field which has grown dauntingly large. The folks complaining about Glasvegas or Kasabian being on the list aren’t doing so soley because they think those acts are a bit rubbish, but because they can think of two, four or ten acts who would all be more deserving of a nomination. Indeed, there are a great number of artists who’d have a right to feel aggrieved at not being on the shortlist: The Super Furry Animals‘ 9th record was a typically creative return; Camera Obscura produced a lovely album of doomed-love pop songs; James Blackshaw underscored how he’s one of the most talented composers in the country; there were great folk albums by Emmy the Great, Caroline Weeks & Blue Roses, some filthy punk from Future of the Left and the best Manic Street Preachers LP in over a decade. Even now, someone might come along and chide me for missing someone out, and they’d be right. The point is that the size of the shortlist belies the extent of the quality & creativity in the British music scene, and as such isn’t doing enough to either represent or promote it.

They don’t claim to be representative, of course – merely to pick the best albums of the year – but that too is part of the problem. The insistence on diversity of genre on the Mercury judge’s part is admirable, but has the consequence of limiting the public’s knowledge of those genres to what they stick on the list every year. I’m not even sure Lisa Hannigan’s record is even the best folk album of the year, let alone an album of the year, but it’s the only folk album on the shortlist. Likewise, most people will never know if there’s any British jazz/soul/rap which is as good or better than Speech Debelle‘s delightful debut, because by including only one example from that genre, you’re not encouraging further exploration or curiosity.

If it really wants to represent the breadth & diversity of British alternative/independent music, the custodians of Mercury Prize would do well to quit fetishising the one award it hands out and become a lot bigger. By all means offer a prize for best album of the year, but why limit it to that? Why not also have a Mercury Prize for different genres; for folk, jazz, rap, modern classical & maudlin whiteboy indie? Given the extent to which the Mercury Prize is trusted as an endorsement of an album’s quality, it surely couldn’t hurt to spread its endorsements further, for by doing so, you might well succeed in hooking the public up to even more sounds they otherwise would not have heard. Maybe then we’ll see a little less sniping over who is/isn’t on the list, and a little more celebrating about the fantastic stuff we produce.

Selected Reading (22/07/09)

July 22, 2009 at 7:21 am | Posted in Misc. | Leave a comment-

In Nigeria, Eamon Kircher Allen finds some of the folks behind those internet email scams.

-

Simon Jenkins objects to the panic over swine flu.

-

Johann Hari defends Sasha Baron Cohen’s new cinematic creation, Bruno.

-

In Vanity Fair, Christopher Hitchens savages Gordon Brown & the Labour Party.

-

Is North Korea helping Burma to go nuclear?

- Robert Manning considers the prospect of deglobalisation.

- Spencer Ackerman finds Daniel Pipes – one of Melanie Phillips’ favourite ‘journalists’ – accusing the Obama administration of taking its orders from the Palestinians.

- Ezra Klein on the Obama administration’s strategy to get a deal on health care.

- Noah Efron on the recent riots in Israel.

- And The Onion gets ‘sold’ to the Chinese.

The ‘Broken Society’ vs ‘Back to Basics’

July 21, 2009 at 8:56 pm | Posted in British Politics, Conservative Party | 3 CommentsI suspect I wouldn’t agree with CentreRight’s allonymous blogger Melanchthon on very much at all, but ever since ConHome gave him a platform for his unique brand of 16th century theology , he’s at least made for a consistently provocative read. Over the weekend, Melanchthon produced a right-wing critique of the Conservative Party’s ‘Broken Society’ rhetoric, arguing that the angle team Cameron has taken on social dysfunction is far too narrow and too focused on playing to the public’s perceived self-interest:

We often talk as if the problem about divorce, drunkenness, drug addiction, the incredible proportions of children from care going on to be criminals, and so on were problems because they cause harm to the rest of us. I understand the reason IDS and others frame the matter that way. They want to be seen to have escaped from moralising and to appeal to people’s self-interest because the moralising route seems to have failed.[…]

We must not think that the proper reason for addressing the needs of the Broken Society is only that, unaddressed, it might interfere, for a moment, with our decadent, empty and meaningless thrill-seeking. The wickedness of our Broken Society is only our own wickedness (yes, mine as well) drawn in vivid colours on a canvass large enough for all to see. It should not be that we address the needs of the Broken Society only because to do so suits our own selfish and nihilistic purposes. We must do so as part of trying to change ourselves. We must condemn the Broken Society because to do so is right and loving and good.

So by seeking to describe the ‘Broken Society’ only in terms of those ‘social evils’ which intrude upon the law-abiding majority, Melanchon essentially argues that Cameron has ripped the morality out of his crusade, creating a campaign which is more transactional than it is rooted in the values of religious conservatism. For him, the party isn’t calling for social change because it is moral and good; merely because it will save the state money & make us a little safer.

It’s a fascinating critique, and one which should remind those with a more liberal outloook of the subtle but important differences between this and the abortive ‘Back to Basics’ campaign that it superficially resembles. It is, in fact, a much cleverer creation, and one which has already resonated far more widely with the public than you saw in 1993.

Looking back, I think one of the problems with Major’s ‘Back to Basics’ speech was that it was too heavy on maudlin generalities to really capture the public’s imagination. The following passage, for example, is positively drenched in a sense of ennui, & nostalgia for some imagined golden age.

I think that many people, particularly those of you who are older, see things around you in the streets and on your television screens which are profoundly disturbing. We live in a world that sometimes seems to be changing too fast for comfort. Old certainties crumbling. Traditional values falling away. People are bewildered. Week after week, month after month, they see a tax on the very pillars of our society – the Church, the law, even the Monarchy, as if 41 years of dedicated service was not enough. And people ask, “Where’s it going? Why has it happened?”. And above all, “How can we stop it?”.

Now compare that with these remarks David Cameron made in a speech last year:

“Whether it is knife crime or any other symptom of our broken society, we will repair the damage by treating not just the symptoms but the causes too. I want the strength of our commitment to inspire faith; faith that our present social breakdown is not inevitable; that this is not a one-way street, faith to replace the disbelief we feel as it dawns on us that we are living in a country where being stabbed is no longer the dark make-believe of crime fiction but the dreadful reality of our children’s daily lives.

“And there is a thread that links it all together. The knife crime. The worklessness. The ill health. Above all, the wasted lives: “A sixteen year-old boy stabbed in north London; a sixty year-old man sitting around in Easterhouse who’s never had a job. A twenty-eight year-old woman stabbed in south London; a forty-eight year old woman dying from heart disease in Gallowgate.

“The thread that links it all together passes, yes, through family breakdown, welfare dependency, debt, drugs, poverty, poor policing, inadequate housing, and failing schools but it is a thread that goes deeper, as we see a society that is in danger of losing its sense of personal responsibility, social responsibility, common decency and, yes, even public morality.

Where Major’s rhetoric was fogged-over by vague moralising about returning to the ‘neighbourliness, decency & courtesy’ of the past, Cameron is more precise, identifying the specific symptoms of the ‘Broken Society’ and arguing that only by reducing them can we have a happier, more equitable future. Significantly, all of the social evils he lists (however indirectly) either costs the state money or causes harm to law-abiding people, and he is not asking for anything more from the British people than those things most of us already do.

Just as Major & Cameron’s ideas are framed very differently, I suspect the consequences of the two speeches will also be very different. Thanks to the fuzziness with which ‘Back to Basics’ was sold, Major unwittingly committed the Conservatives to leading the country to a kind of moral reformation. Unfortunately for him, by doing so it became fair game to scrutinise the character of his cabinet, and when a number of those ministers failed to stand up to that scrutiny, it fatally undermined the project he was trying to sell.

I think Cameron is avoiding this trap because he’s already been a lot more clear about what his ‘Broken Society’ is. He’s not asking for piety or even for the vast majority of us to change our ways of living; he’s not going to chide us for discourtesy, committing infidelity or being neglectful neighbours, since his real broken society is in the actions of the teenage mother, the drug addict and the ASBO youth. To that end, some newspaper discovering that a member of his cabinet had once smoked a spliff or comitted an affair wouldn’t undermine the project, for their actions never fell under his description of the ‘Broken Society’ in the first place. Whether it was intended or not, that’s a very clever way of avoiding the ‘hypocrisy trap’.

By suggesting that the Conservatives’ rhetoric should be based on moralism rather than the public’s perceived self-interest, I think Melanchthon’s approach is much closer to the Major approach, and is therefore at risk of suffering the same fate. Whilst the partisan in me has no problem with the Tories overplaying their hand in this way, I suspect that genuine Conservatives won’t want Cameron to change his winning strategy one bit.

Gang culture, territory & fear

July 20, 2009 at 3:42 pm | Posted in British Politics, Crime | 6 CommentsNothing brings Britain’s social problems into focus like seeing them on your doorstep. What might seem abstract when described in Home Office documents or reported from unfamiliar places becomes a lot more intimate when it’s set somewhere you know: full of landmarks you’ve visited, people you might’ve met, folks who speak with the same accent or walk the same streets as you.

So when I read Mark Townsend’s report on the rise of gun & gang culture around the Burngreave & Pitsmoor areas of Sheffield, I was always going to react to it differently than if it’d been set in somewhere like Manchester, Liverpool or the North East. I can’t claim to know these neighbourhoods intimately, but my emotional attachment to the city means I probably can’t react as impartially or dispassionately as I would if it were set somewhere else.

But whilst responding emotionally to problems which need rational policy solutions isn’t always helpful, it’s also often unavoidable. Watching YouTube videos made by members of the various ‘postcode gangs’ can be a thoroughly depressing experience: seeing kids as young as 13 drinking beers, lighting up joints, posing with enough knives & firearms to overthrow the city council, and filming tributes to slain friends. To be honest, if I didn’t have an emotional reaction to this parade of low ambition & self-destruction, there’d be something wrong with me.

In fact, when we think about the dangers for kids in our inner cities, it wouldn’t hurt to see emotion as a useful tool for analysis. Whilst there are always structural explanations for poverty, unemployment, social exclusion & family breakdown, what leads these young people into situations where they put their lives or other people’s lives at risk is a toxic brew of bravado & fear. It’s the combination of these which leads kids to join a gang, get hold of a weapon, threaten someone with a knife or gun, and then eventually use one. As Townsend’s report indicates, the wars in Pitsmoor & Burngreave aren’t over control of drug turf like you might find in Manchester; they result from petty beefs which escalate into murders because they’ve never learnt how to control their emotions.

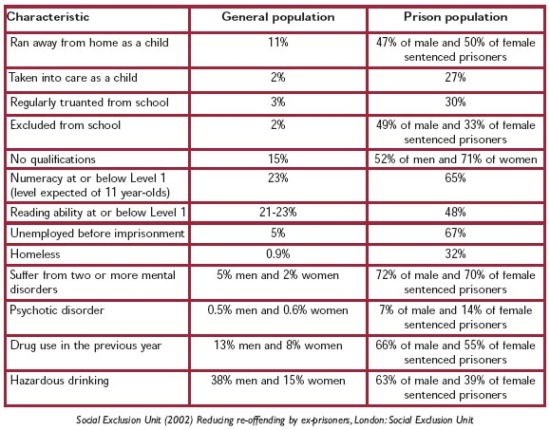

The controlling, constraining nature of fear alters kids’ behaviour in other ways, too. Last year, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation conducted a study to see what impact ‘territorality’ (basically a nicer way of saying ‘ghettoisation’) had on the lives of young people. They asked kids to draw maps of their neighbourhoods and label which places they felt were safe to go and which were not:

As you can see from these pictures, pieces of land which may be no bigger than a single square mile can be written-off as ‘no go areas’, boxing these kids in to their gang-defined safety zones. As a result, they might not be able to access social services, leisure activities, schools, work or relationships with people from other areas. Their postcode becomes their world, and straying too far from it must feel like sailing off the edge of a flat earth.

So when we think about how we might reduce the harms of gang culture and the number of youngsters being stabbed or shot, of course we should consider those long-term structural aspects which social scientists have talked about for decades, but we should also think about practical ways of reducing the fear which causes many of these kids to join gangs, to rarely leave their small, ‘safe’ postcodes, to carry weapons and cause harm to others. This situation won’t get better with more crackdowns or ‘get tough’ pledges, but if you can make the streets seem a little less terrifying, you might just same some lives.

Selected Reading (15/07/09)

July 15, 2009 at 9:30 pm | Posted in Misc. | 6 Comments-

To add some analysis which runs contrary to my rather downbeat assessment, Peter Bergen reckons Afghanistan is more winnable than people think.

- Meanwhile, Eric Martin reviews the situation for himself.

- In the 21st century, there are half a million slaves living in Mauritania.

- I said a few posts back that Mother Jones’ collection of dissenting pieces on the war on drugs was worth a read. If you can’t be bothered to read everything, this editorial makes the central argument really well.

- Thomas Mucha looks at the political violence & civil unrest which has sprung up around the world since the global financial crisis.

- Laura Woodhouse describes how a lack of confidence can sometimes be an impediment to cracking accepted stereotypes & gender roles.

- Bill Conroy on the American lobbyist hack who’s started shilling for the junta in Hondouras.

- It’s a bit old, but awesome culture mag PopMatters turned 10 at the end of last month. To celebrate, they revisited some of the most memorable albums of 1999 and pondered what they revealed about pop culture at the turn of the century.

- And since we can’t be doom-laden all the time, here’s a happy story about a 15-year-old flying an 87-year-old across America.

Selected Reading (14/07/09)

July 14, 2009 at 8:55 pm | Posted in Misc. | Leave a comment- In news which isn’t news… Mexico’s drug war is still failing.

- Brad Plumer discusses whether American chickens are being pumped with far too many antibiotics.

- At Feministing, Vanessa discusses a piece on the gendered messages in girls’ video games.

- Chutzpah alert: The president of a state with a history of genocide denial has the audacity to think he’s in a position to start throwing the g-word at other countries.

- Harry’s Place’s Edmund Standing authors a report into the BNP’s online activities.

- Mark Easton discusses the DWP’s strategy for an ageing population.

- Stephen Faris wonders whether the next conflict between India & Pakistan could be caused by… climate change.

- And Everett True pens a great tribute to deceased rock critic Steven Wells

No simple solutions for Afghanistan

July 13, 2009 at 9:12 pm | Posted in International | Leave a comment

I’ll confess to being a bit indecisive about the war in Afghanistan and the regional strategy being pursued by the Obama administration. Whilst I think Sunny’s case for continuing to fight Afghanistan’s heavily-armed, well-organised & utterly mercenary militants is a good one, I’ve never really had an issue with the justification for our involvement there. Instead, I just harbour a deep scepticism about whether the sort of ‘victory’ expected by politicians and the public is within the capability of coalition forces.

I worry about the militarisation of humanitarian aid, about the feeble nature of the Karzai government and about how the country seems ungovernable by a single centralised entity. I worry about how the vast & porous border with Pakistan is allowing countless tourist-terrorists to slip between the two countries, and whether the Pakistani army is either inclined or equipped to disband/eliminate the country-hopping militants within its own borders. As Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg has stated, it’s hard to escape from the conclusion that (from a British point of view, at least) our mission there is over-ambitious and our troops are under-resourced.]

But whilst I still haven’t tethered myself to a firm position on this protracted, putrid war, I can still spot a shabby piece of analysis when I see one. Peter Preston does manage to land a few soft punches in his diatribe against our involvement in the region. For one, he’s right to dismiss the Miliband argument about ‘fighting them over there instead of fighting them over here’ as the Bush-esque scaremongering that it is. Whilst there would obviously be security implications if Afghanistan regressed back to a Taliban-ruled dictatorship, the prospect of that leading to another 9/11 (or even Madrid or 7/7) is seriously overstated. Preston’s also right to point out that Afghanistan is only one part of a much broader regional picture, of which Pakistan is central.

But that’s about as close as Preston gets to helping us see a way out of our current malaise. For him, Afghanistan is a doomed, futile endeavour; an entity too disparate & diverse to be held together by a single state, and where our involvement is only multiplying death & resentment. So we should admit defeat, withdraw, and then hope that Pakistan manages to get a grip on its own militants. This would help the Afghans because:

If Taliban land is cordoned off, isolated, consigned to its own devices, then it won’t survive for long. And if the Pakistani army, without constant western intervention, is left to do what it has to do, then Islamabad opinion will stay focused on its own future, under so much threat from within.

For all the daydreaming about what might be achieved without western intervention, it should be remembered that the Pakistani military’s offensive in areas like Swat was only made possible with billions in American aid and the incessant arm-twisting of American diplomats. There are still people in the Pakistani military who support these insurgent groups, more who’re only motivated by hatred of India, and even more who’re unused to the kind of counter-insurgency tactics required to regain lost territory. That’s before we even consider the consequences to what’s left of Afghanistan’s human rights if we allow the misogynistic, anti-education, anti-science Taliban to return to national power.

Then there’s the small matter of a border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Preston admits this vast stretch of land is ‘porous’ but doesn’t regard it as a problem. However, he then seems to think that the Taliban’s land can be ‘cordoned off’, presumably militarily. This is either imprecise writing or very muddled thinking. As Sunny points out, defeat and withdrawal from Afghanistan would have a direct impact on Pakistan’s security and threaten to make an uneasy truce with India even more delicate. If Preston has considered that his idea may have its own negative consequences, he certainly doesn’t share those considerations with his readers

We might well reach the stage where we’re forced to admit that no more good can be achieved in Afghanistan and that the least worst solution for them and us is to withdraw and hope for the best. But the trouble with so many of the ideas offered by the commentariat is that they’re put forward as though there are easy solutions to this malaise. If only wishing made it so.

Image: MIAN POSHTEH, AFGHANISTAN – JULY 13: U.S. Marines with the 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, RCT 2nd Battalion 8th Marines Echo Co. walk through a field on patrol on July 13, 2009 in Mian Poshteh, Afghanistan. The Marines are part of Operation Khanjari which was launched to take areas in the Southern Helmand Province that Taliban fighters are using as a resupply route and to help the local Afghan population prepare for the upcoming presidential elections. (Source: Getty)

Selected Reading (12/07/09)

July 12, 2009 at 7:59 pm | Posted in Misc. | 2 CommentsJust a handful of weekend leftovers:

-

The NYTimes gets around to doing some journalism, discovers a CIA project concealed by Dick Cheney. The Democrats may grow a pair and conduct investigations.

-

Green shoots? Robert Reich isn’t optimistic.

-

Anna Husarka complains about the growing militarisation of humanitarian work in Afghanistan.

- Brad Plumer reports on the new research into sea level rises.

- And the Ukraine’s decided that a recession is a good time to kill some industries, so pornography & gambling have been banned.

Meet the prisoners

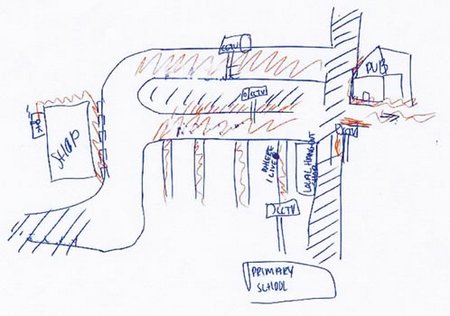

July 12, 2009 at 7:18 pm | Posted in Prison Reform | Leave a commentReading the Prison Reform Trust’s latest Factfile (PDF) this afternoon, this table really stuck out:

There are 83,000 people currently incarcerated in England & Wales. Of that number, I’d wager all the money in my pockets that not one of them grew up wanting to do this. Like us, they will have grown up dreaming impossible things; fantasising about future fame or heroics; quietly relishing the adventures of adulthood. Sure, few of us ever come close to achieving the dreams we had as children, but we can at least modify them: replace ‘Premiership footballer’ with ‘a nice house and a happy family’, or ‘astronaut’ with ‘earning just enough to live in comfort’. But for many of the people represented in this table, those hopes have long since disappeared: crushed by violence, abuse, broken homes, drugs, alcohol, poor education, mental disorders, homelessness. Of course inmates bear the ultimate responsibility for the crimes they commit, but the experiences & attitudes we encounter on our way to becoming adults are inevitably shaped by others. For better or worse, we all make each other what we are.

So the starting point for a belief in the need for prison reform is that whilst there are some irredeemably cruel, cynical, evil people in our jails, they are also in the minority. The rest may have lead tough lives or made bad choices (sometimes both), been controlled by a drug habit or hampered by a failure to read, write or offer qualifications in a crowded jobs market. But they are salvageable, and if we replace the tired old dichotomy of ‘tough’ & ‘soft’ (because true reform would require aspects of both) with something which simply seeks to provide a pathway out of crime, we’d not only have a much healthier society, but a reduced burden on the organs of the state.

Create a free website or blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.

So what might these events reveal about the theory of change which Barack Obama espoused from the first day of his campaign for president? Well, on the one hand, the gay rights movement is an example of a group which has already banded together, already organised, already contributed a great deal to American political life, and yet still can’t get their few simple wishes granted – even under the most liberal president of modern times. Does that not reveal the limits – maybe even the futility – of Obama’s vision of grassroots political campaigning?

So what might these events reveal about the theory of change which Barack Obama espoused from the first day of his campaign for president? Well, on the one hand, the gay rights movement is an example of a group which has already banded together, already organised, already contributed a great deal to American political life, and yet still can’t get their few simple wishes granted – even under the most liberal president of modern times. Does that not reveal the limits – maybe even the futility – of Obama’s vision of grassroots political campaigning?